Keybot - Exploring Research Through Design

Introduction #

The research interaction project, known as Keybot, addresses the challenge of limited key access in shared studio workspaces at design and art schools. Typically, only a single shared key is available, causing repetitive and frustrating interactions for individuals seeking entry. To facilitate this process, I designed and constructed a device to automatically notify colleagues of someone's presence, indicating that the doors are already unlocked. By simply placing the key in its usual location, the device handles communication automatically.

The aim of Keybot is to replace cumbersome human interactions with a robotic solution while maintaining a sense of communal connection. Initially, one might assume that reducing human-to-human interactions, even the annoying ones, could diminish the team's dynamics, which is not the desired outcome. Therefore, the tension lies in designing a device that automates the tedious aspects while nurturing the communal atmosphere within the shared workspace.

Research Through Design #

In the spring/summer of 2023, I participated in the studio course titled "Research with Yo-Yo Machines – exploring context, form, and function" led by visiting educator Alma Leora Culén. This course delved into the realm of Research Through Design (RtD) and interaction design through a multifaceted approach. It was comprised of theoretical studies, hands-on workshops for ideation and creation, and practical exploration of the do-it-yourself (DIY) playful communication devices known as Yo-Yo Machines. The present project serves as the outcome of this course.

fig.N: Knock Knock Yo-Yo Machine

Identifying an Opportunity: Streamlining Access to Shared Workspaces #

As a student at FaVU, a fine arts and design school with discipline-oriented studios, I observed a problem regarding access to shared workspaces. Each studio is based in a physical space where members can work, study, and socialise. However, despite the presence of up to 30 members in each studio, only a single key is available at the reception. This situation requires individuals to check out the key at the reception every time they want to enter the studio, resulting in unnecessary time and effort, particularly when someone is already present inside the studio.

In Design Studio 1, where I'm a member, frequent visits occur but not on a regular schedule that can be predicted solely by time. Moreover, our studio, along with eight others, is located in a separate building from the reception, amplifying the inconvenience of back-and-forth trips to borrow the key.

This limitation led to an inconsistent pattern of communication within our studio. However, responses were not always timely or reliable. Recognising the negative impact of these disruptions and the need for a more streamlined and pleasant solution, I began contemplating the development of an automated key-sharing process based on the emergent behaviour within our group.

In summary, this initial observation of the inefficiency and inconvenience caused by the single shared key system at FaVU prompted me to explore the design and development of the Keybot interaction design project. The project aims to address the problem of key access in shared workspaces by leveraging existing communication practices and creating an automated solution for letting peers know about your presence.

Studies #

The Tension of Automation #

Automation has long been seen by some as a force that erodes humanity, individuality, tenderness, and genuine connections. Throughout history, our society has regularly raised concerns about automation. Currently, the focus of scrutiny is Artificial Intelligence (AI). Will AI lead to increased control or more freedom? Will it create more jobs or fewer jobs? And most importantly, will it render humans obsolete? These discussions typically revolve around the broader impact on society, but what about the impact on our interpersonal relationships, our sense of community, and our everyday human interactions?

Bringing the focus back to my project, I ask a fundamental question: Can automating even a seemingly innocuous task like key sharing diminish the qualities of a community by eliminating various micro-interactions? Furthermore, can humanist interaction design mitigate these negative effects and perhaps even create new opportunities for fostering stronger bonds within a group?

Humanist Technology from Emergent Behaviour #

Instead of imposing technology-driven changes on people's behaviour, I believe that technology should adapt to accommodate people's existing behaviours. Thus, my design process for Keybot began by examining the communication patterns surrounding key sharing that were already established in our studio.

The most prevalent pattern involved individuals sending a message to the group Discord server when they were en route to the studio, inquiring about whether someone was already present. However, this method proved unreliable as not everyone had notifications enabled or wanted to be distracted from their tasks by responding promptly. If a response arrived at all, it often arrived too late. Nevertheless, on the occasions when this method succeeded, it worked seamlessly. To capture this successful dynamic, I collected messages announcing members' presence in the shared space and repurposed them as messages generated by the automated system. By utilising an array of human-written messages, my intention is to foster a more friendly and personable experience compared to an automated, repetitive response.

Another, less frequent pattern proved to be even more useful. Some individuals would send notification messages immediately after unlocking or locking the studio. This enabled anyone on their way to open the group server and check the current status in the appropriate chat channel. I aimed to build upon this pattern and automate the process.

Chat as a platform #

Smartphones and apps are currently the go-to solutions for addressing communication challenges. With these ubiquitous internet-connected devices always at our disposal, they serve as versatile platform for various tools. The prevailing approach in mainstream technology development revolves around creating dedicated apps due to their widespread usage.

However, I contend that chat, an integral part of maintaining and organising a group of humans in the digital age, can also be a platform for prototyping technology. Instead of relying on complex coding, prototypes can be built using social conventions and simple text formatting. I have witnessed and participated in using chats as platforms for various purposes such as reading clubs, habit trackers, diaries, complex polls, wikis, directories, and even art projects. Over time, intentionally or organically (or a combination thereof), the chat evolves and transcends its original purpose.

fig.N: Reading club inside a chat

The key element in developing tools within a chat environment lies in establishing shared social conventions. The group of users must reach a consensus on how and when the chat transitions into a distinct tool, determining its designated functionalities and behaviours.

Discord Bots #

Discord, a chat application, offers an exceptionally fertile environment for unconventional uses. Users can establish private or public servers, each comprising multiple chats known as channels, which are further compartmentalised into categories. This setup, coupled with the flexibility of markup text formatting, channel mentions, user mentions, and emoji reactions, provides a highly adaptable digital substrate. Moreover, an additional layer of customisation is afforded through the utilisation and sharing of bots—programmable robot users capable of performing a wide range of tasks. These tasks can span from playing music in voice-chat to autonomous server moderation or even interfacing with entirely separate digital services. In the development of Keybot, I have harnessed the power of a Discord bot as the underlying communication technology, sidestepping the need to develop another app.

Single-purpose Computers #

The majority of our computing activities, including chatting, occur on general-purpose devices such as desktops, laptops, tablets, and the aforementioned smartphones. These devices are capable of performing a wide range of tasks, offering hyper-generalized interfaces as a result. They have become indispensable tools for participating in society and resolving everyday challenges.

In contrast, single-purpose or special-purpose computers occupy the other end of the computer design spectrum. These computers are purpose-built with a singular objective in mind, providing a specialised interface tailored to specific interactions. This singular focus enables simplicity, as seen in Dieter Rams's devices, and tactility, exemplified by retro gaming cabinets. The limitations imposed by their singular function allow for a greater emphasis on the quality and aesthetics of the interaction.

fig.N: Specialised computer interface for manual atmospheric reentry on the Soyuz spacecraft

From a physical environment design standpoint, the concept of the single-purposed Keybot computer drew inspiration from an existing feature in our studio—a simple nail positioned next to the door where the key should always hang. By leveraging this analog nail, I positioned my device in the same location, striving for near invisibility to minimise friction and facilitate a seamless transition to the new device.

fig.N: The original nail

Exploring Interactions #

Chat Connected Key Sensor Interaction #

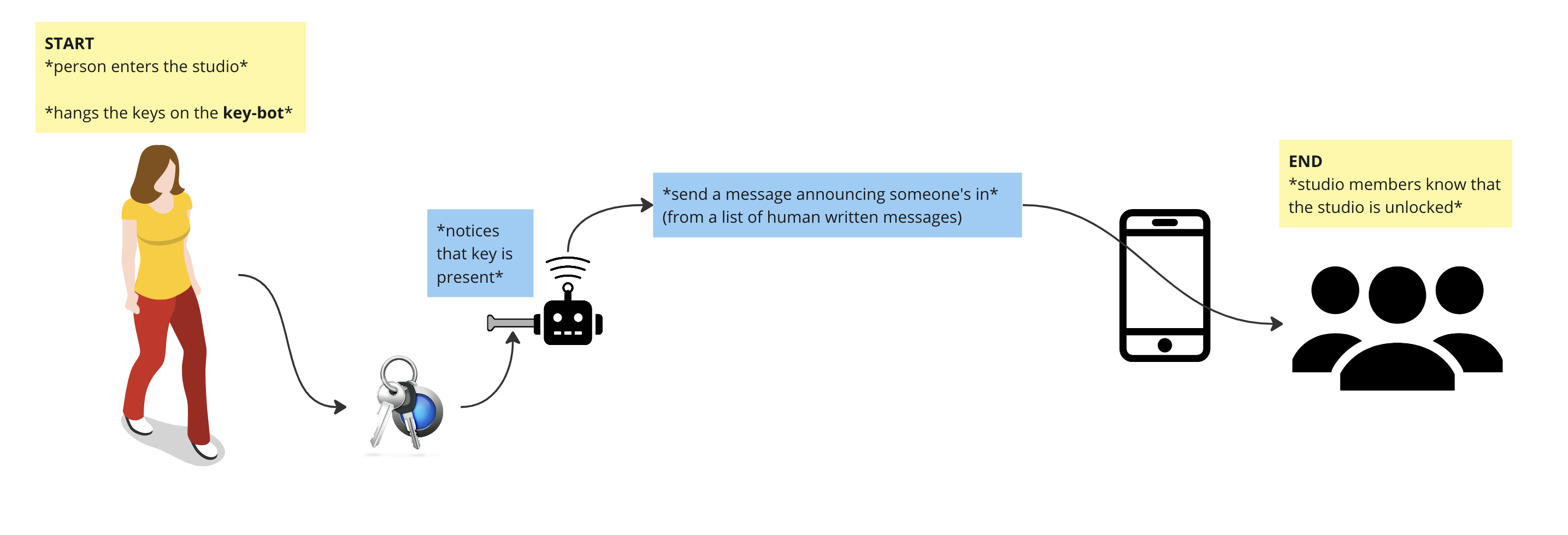

The core interaction of Keybot makes use of a sensor designed to detect the presence of a key. Once the sensor detects a key hanging of it, a message that is sent to a specific Discord chat channel, which serves as the platform for interacting with the device over the internet.

fig.N: Interaction on entry

Applying the same principle, when the sensor no longer detects a key, it assumes that everyone is leaving the studio, and that the key will be returned to the reception. Studio members are notified of this through a message in a designated chat channel, just as with the on entry interaction described in fig.N.

Accounting for Human Error #

During discussions with my fellow studio members, valuable feedback was received regarding the potential for human error in remembering to hang the key. Right now, it is possible to unintentionally take the key home if it is left in one's pocket, which is frustrating. This could also pose challenges for the functionality of Keybot.

To address this issue, I explored various solutions that would account for human error. I dismissed options such as a doorframe sensor or an electromagnetic lock as they were either too intrusive or did not fully resolve the problem.

At one point, I became engrossed in researching different types of clocks. My hypothesis was that incorporating a secondary function into the device could increase the likelihood of people noticing it. While the idea of constructing an alternative clock still captivates me, it was not feasible within the project's timeframe.

Knock Interaction Inspired by Yo-Yo Machines #

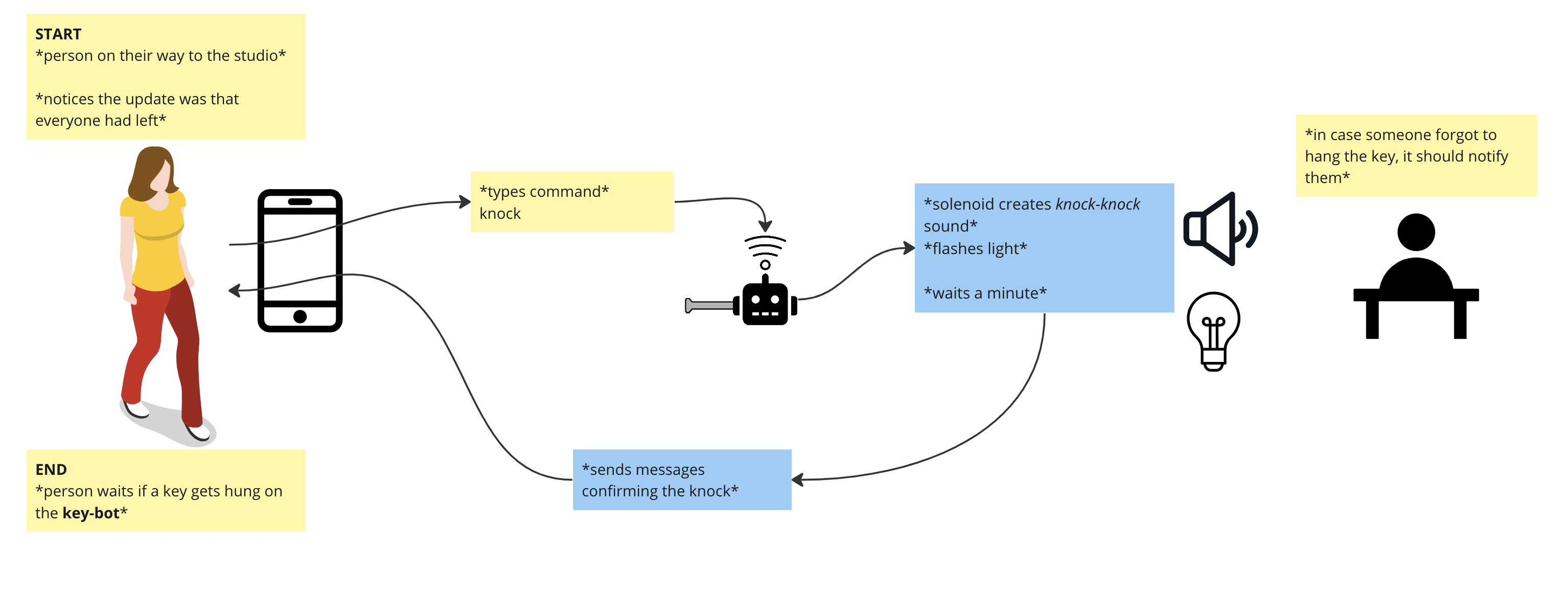

In the final design of Keybot, I drew inspiration from the Yo-Yo Machines project, specifically the "Knock-knock" machine. This machine utilises a piezo microphone to listen to human knocks and replicates the pattern on a paired machine using a solenoid. Both machines can function as both the input and the output.

The symbolism of knocking, as a means of communication through closed doors, resonated with me, and I decided to adapt this technology for a slightly different purpose. In the Keybot device, the solenoid is also employed to produce a knocking sound, serving as a way to capture the attention of someone in the studio. If you are on your way and there is no notification of the doors being unlocked, you can send a message containing the word "knock" in the designated chat. In the event that someone is already in the studio but has forgotten to hang the key, the sound, accompanied by a flashing blue LED, aims to grab their attention, prompting them to hang the key.

fig.N: Knock Interaction

Putting It Together In Practice #

The brain: ESP-32 #

The ESP-32 serves as a compact internet-connected computer capable of powering and controlling electrical components. Technically speaking, it is a low-cost, low-power system-on-a-chip microcontroller with integrated Wi-Fi. This microcontroller was also employed in the Yo-Yo Machines project. In the making of Keybot, I specifically worked with the ESP32-DevKitc-V4 development board.

Capacitive Touch Sensor #

A capacitive touch sensor operates by detecting changes in capacitance caused by the proximity or touch of a conductive object, such as a finger or metal key.

The ESP-32 module is utilised to measure the capacitance of the touch sensor, determining the presence or absence of a conductive object. This can be accomplished using the built-in capacitive touch sensing hardware of the ESP32 or by connecting an external capacitive touch sensor to the GPIO pins of the module. In my case, I connected a screw to serve as a place to hang the key by its keyring.

Generating Light and Sound #

Drawing inspiration once again from the Yo-Yo Machines project, I incorporated similar hardware components, including an addressable RGB LED and a small MOSFET module. The MOSFET module facilitates control of a small push-pull solenoid, which produces the knocking sound as it bangs against the wall of the casing.

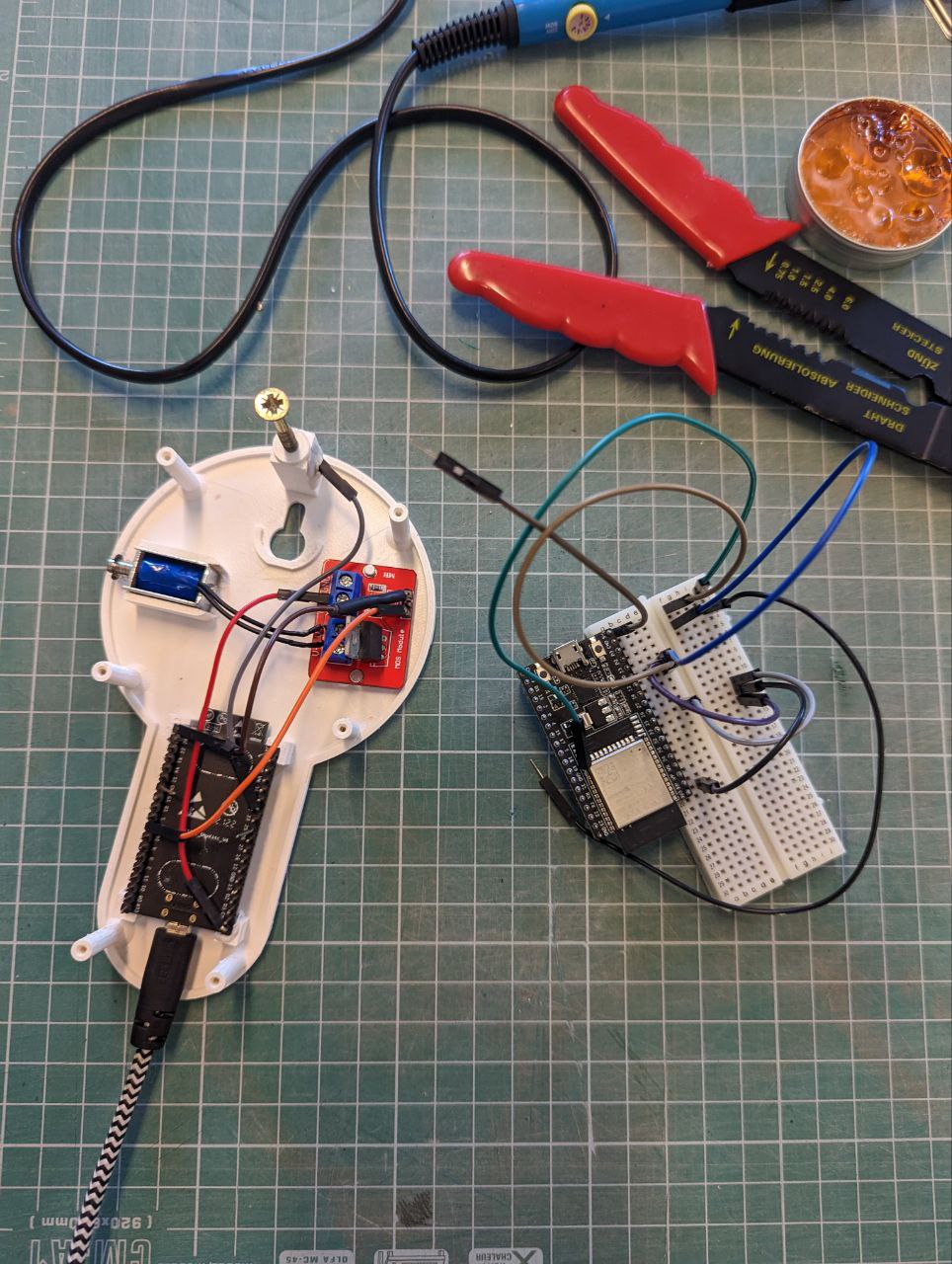

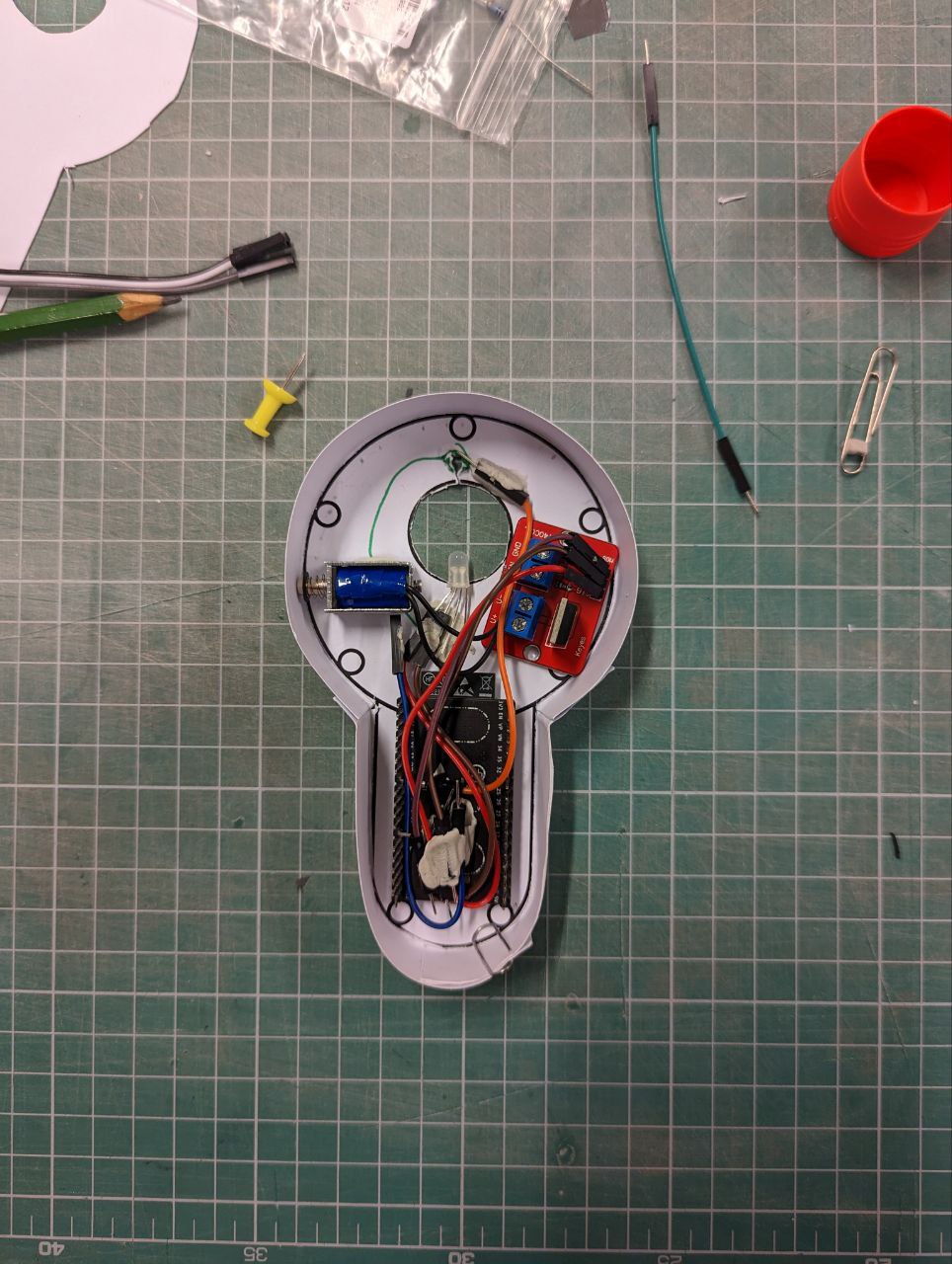

Wiring It All Up #

In the early prototyping stage, a breadboard and some Dupont cables were used to test the functionality of the hardware and firmware. In the final prototype, a combination of Dupont cables, and traditional soldering methods take care of the electrical connections.

fig.N: Prototyping

Coding The Firmware #

The microcontroller can be programmed using the C programming language. For this project, I chose to code in the ESP-IDF framework developed by Esspressif, the same company that manufactures the ESP-32 microcontroller. I made this decision because of the availability of an open-source library designed for the ESP-IDF framework, which simplifies the interaction with a Discord bot. Additionally, I leveraged code snippets from various open-source example projects to control the other components, significantly streamlining the firmware development process.

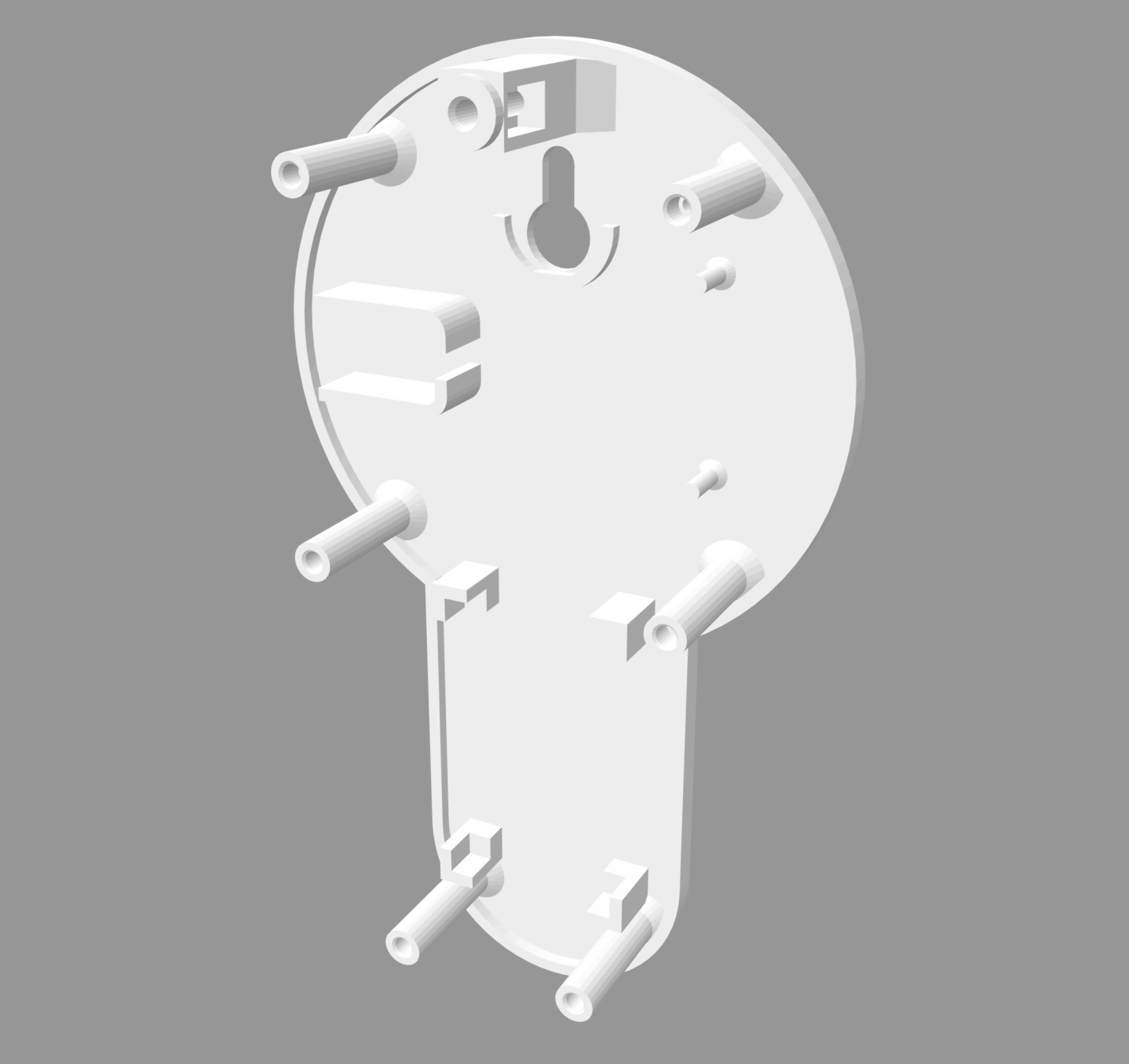

🚧 Making The Casing #

I opted for a 3D printed casing for the device, enabling me to quickly obtain a sturdy and precise prototype. I employed a CAD software to design the casing, and the final 3D model is publicly available on the internet. I also utilised paper and styrofoam mockups, allowing for a more hands-on approach to solving any model-related issues during the design process.

fig.N: Paper Mockup Of The Casing  fig.N: Bottom Half Of The Casing Model

fig.N: Bottom Half Of The Casing Model  fig.N: Top Half Of The Casing Model

fig.N: Top Half Of The Casing Model

The initial 3D print had some imperfections, as expected, prompting me to revise and refine the design accordingly. Furthermore, I conducted a poll within the studio's Discord server to gather opinions on whether to keep the "KEY BOT" logo. The response was overwhelmingly against it, which pleased me, as I shared the same sentiment.

fig.N: First Printed Version Of The Casing

- [ ] ADD: photos of the second version

Conclusion #

From the particular to the universal #

I believe that by focusing on immediate problems, challenges, and tensions in your surroundings, the proposed design solutions can achieve the highest quality. The outcome of designing out of one's own experience can be described as a version of the "ultimate particular"[1]. From this particular context, a more universal artefact can be derived and applied effectively in a multitude of situations.

The Keybot device emerged from a specific context within design and art studios at universities. However, with a bit of imagination, it can be adapted to a wide range of situations where signalling one's presence is crucial. For instance, instead of being triggered by hanging, the capacitive sensor could be activated by the touch of an elderly person who has just arrived to participate in a workshop.

To encourage further modification and exploration, I have made all the code, 3D models, parts list, and instructions available on the GitHub platform. These resources are provided under the permissive open-source license GPL3, allowing others to build upon and customise the Keybot device according to their own requirements and contexts.

Systems Thinking Perspective #

I want to acknowledge my own criticism of this project, which is that it doesn't address the underlying issue of having only one key available; instead, it focuses on alleviating the symptoms. Alternative approaches could have involved attempting to change the school's system or creating unofficial copies of the key for everyone. It's possible that one of these scenarios may occur in the future, rendering Keybot obsolete. However, despite considering this perspective, I am not overly concerned. This project has provided valuable learning experiences and has been a highly enjoyable endeavour.

Reference: #

Fallman, D. (2008). The Interaction Design Research Triangle of Design Practice, Design Studies, and Design Exploration. Design Issues, 24(3), 4-18. ↩︎